Chromophores

A substance is colored when its molecules absorb visible radiations in an uneven way. The apparent color is then the result of these wavelengths that are not or less absorbed. Even if this characteristics is a molecular property, the color is attributed to a so-called chromophore, which can be a given part of the molecule. The color of an organic molecule often comes from electrons that are delocalized over a group of atoms rather than being strongly involved in covalent bonds. Under white light or ultraviolet illumination, transitions between allowed energy levels of these electrons correspond to selective absorption of the incident radiations, responsible for the observed color. In transition metalorganics, the electronic transition takes place between an atomic level of the transition metal and an orbital state of the ligand.

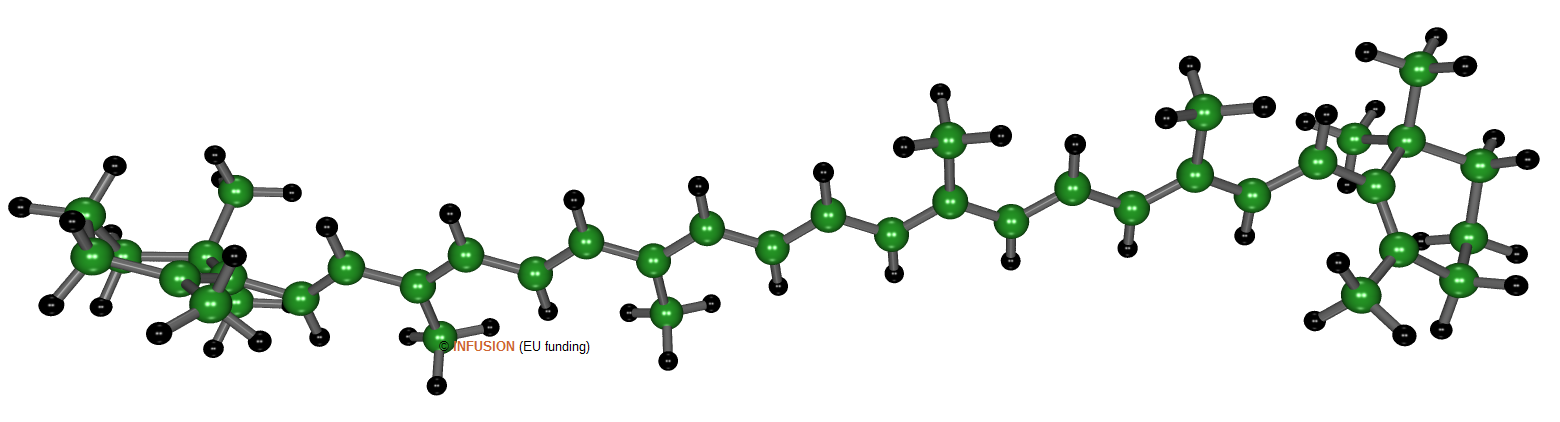

Beta-carotene, a natural pigment with chemical formula C40H56, is a conjugated pi-bond chromophore. As the result of its atomic structure, illustrated above, pi electrons are delocalized over the whole molecule. Electronic transitions between occupied and unoccupied pi levels absorb radiations with wavelength between 400 and 500 nm. The radiations with longer wavelengths produce the characteristic red-orange color.

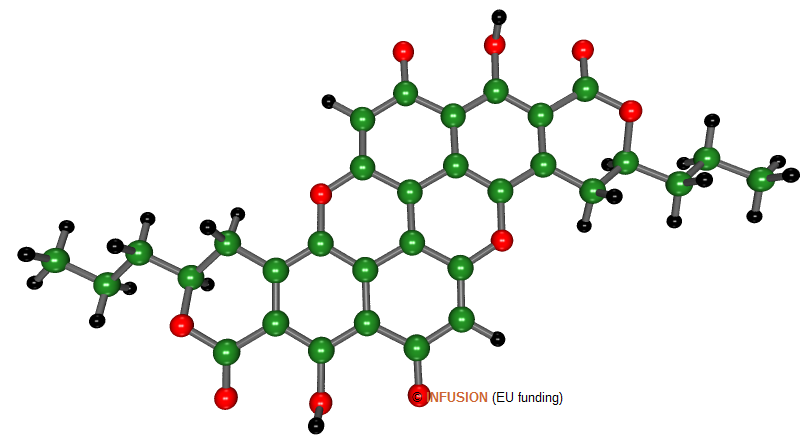

Xylindein (above), with chemical formula C32H24O10, is a natural green-blue dye. The chromophore is the aromatic core of the molecule [1] named PXX for peri-Xanthenoxanthene (set of six hexagonal rings of which two contain an oxygen atom (red balls) in substitution for carbon).

- "Nature'other greens" G.M. Blackburn, New Scientist 19 (1963) 182-184.